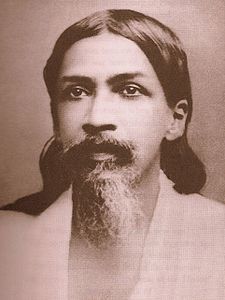

The Life Divine

Book Two

The Knowledge and the Ignorance

The Spiritual Evolution

From Volume 21 and 22 of

The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo

Superior Index Go to the next: Chapter 18

Print Files: A4 Size.

Chhandogya Upanishad.92"The living being is none else than the Brahman, the whole world is the Brahman."

Vivekachudamani.93"My supreme Nature has become the living being and this world is upheld by it. All beings have this for their source of birth."

Gita.94"Thou art man and woman, boy and girl; old and worn thou walkest bent over a staff; ... thou art the blue bird and the green and the scarlet-eyed. ..."

Swetaswatara Upanishad.95"This whole world is filled with beings who are His members."

Swetaswatara Upanishad.96

AN INVOLUTION of the Divine Existence, the spiritual Reality, in the apparent inconscience of Matter is the starting-point of the evolution. But that Reality is in its nature an eternal Existence, Consciousness, Delight of Existence: the evolution must then be an emergence of this Existence, Consciousness, Delight of Existence, not at first in its essence or totality but in evolutionary forms that express or disguise it. Out of the Inconscient, Existence appears in a first evolutionary form as substance of Matter created by an inconscient Energy. Consciousness, involved and non-apparent in Matter, first emerges in the disguise of vital vibrations, animate but subconscient; then, in imperfect formulations of a conscient life, it strives towards self-finding through successive forms of that material substance, forms more and more adapted to its own completer expression. Consciousness in life, throwing off the primal insensibility of a material inanimation and nescience, labours to find itself more and more entirely in the Ignorance which is its first inevitable formulation; but it achieves at first only a primary mental perception and a vital awareness of self and things, a life perception which in its first forms depends on an internal sensation responsive to the contacts of other life and of Matter. Consciousness labours to manifest as best it can through the inadequacy of sensation its own inherent delight of being; but it can only formulate a partial pain and pleasure. In man the energising Consciousness appears as Mind more clearly aware of itself and things; this is still a partial and limited, not an integral power of itself, but a first conceptive potentiality and promise of integral emergence is visible. That integral emergence is the goal of evolving Nature.

Man is there to affirm himself in the universe, that is his first business, but also to evolve and finally to exceed himself: he has to enlarge his partial being into a complete being, his partial consciousness into an integral consciousness; he has to achieve mastery of his environment but also world-union and world-harmony; he has to realise his individuality but also to enlarge it into a cosmic self and a universal and spiritual delight of existence. A transformation, a chastening and correction of all that is obscure, erroneous and ignorant in his mentality, an ultimate arrival at a free and wide harmony and luminousness of knowledge and will and feeling and action and character, is the evident intention of his nature; it is the ideal which the creative Energy has imposed on his intelligence, a need implanted by her in his mental and vital substance. But this can only be accomplished by his growing into a larger being and a larger consciousness: self-enlargement, self-fulfilment, self-evolution from what he partially and temporarily is in his actual and apparent nature to what he completely is in his secret self and spirit and therefore can become even in his manifest existence, is the object of his creation. This hope is the justification of his life upon earth amidst the phenomena of the cosmos. The outer apparent man, an ephemeral being subject to the constraints of his material embodiment and imprisoned in a limited mentality, has to become the inner real Man, master of himself and his environment and universal in his being. In a more vivid and less metaphysical language, the natural man has to evolve himself into the divine Man; the sons of Death have to know themselves as the children of Immortality. It is on this account that the human birth can be described as the turning-point in the evolution, the critical stage in earth-nature.

It follows at once that the knowledge we have to arrive at is not truth of the intellect; it is not right belief, right opinions, right information about oneself and things, - that is only the surface mind's idea of knowledge. To arrive at some mental conception about God and ourselves and the world is an object good for the intellect but not large enough for the Spirit; it will not make us the conscious sons of Infinity. Ancient Indian thought meant by knowledge a consciousness which possesses the highest Truth in a direct perception and in self-experience; to become, to be the Highest that we know is the sign that we really have the knowledge. For the same reason, to shape our practical life, our actions as far as may be in consonance with our intellectual notions of truth and right or with a successful pragmatic knowledge, - an ethical or a vital fulfilment, - is not and cannot be the ultimate aim of our life; our aim must be to grow into our true being, our being of Spirit, the being of the supreme and universal Existence, Consciousness, Delight, Sachchidananda.

All our existence depends on that Existence, it is that which is evolving in us; we are a being of that Existence, a state of consciousness of that Consciousness, an energy of that conscious Energy, a will-to-delight of being, delight of consciousness, delight of energy born of that Delight: this is the root principle of our existence. But our surface formulation of these things is not that, it is a mistranslation into the terms of the Ignorance. Our I is not that spiritual being which can look on the Divine Existence and say, "That am I"; our mentality is not that spiritual consciousness; our will is not that force of consciousness; our pain and pleasure, even our highest joys and ecstasies are not that delight of being. On the surface we are still an ego figuring self, an ignorance turning into knowledge, a will labouring towards true force, a desire seeking for the delight of existence. To become ourselves by exceeding ourselves, - so we may turn the inspired phrases of a half-blind seer who knew not the self of which he spoke, - is the difficult and dangerous necessity, the cross surmounted by an invisible crown which is imposed on us, the riddle of the true nature of his being proposed to man by the dark Sphinx of the Inconscience below and from within and above by the luminous veiled Sphinx of the infinite Consciousness and eternal Wisdom confronting him as an inscrutable divine Maya. To exceed ego and be our true self, to be aware of our real being, to possess it, to possess a real delight of being, is therefore the ultimate meaning of our life here; it is the concealed sense of our individual and terrestrial existence.

Intellectual knowledge and practical action are devices of Nature by which we are able to express so much of our being, consciousness, energy, power of enjoyment as we have been able to actualise in our apparent nature and by which we attempt to know more, express and actualise more, grow always more into the much that we have yet to actualise. But our intellect and mental knowledge and will of action are not our only means, not all the instruments of our consciousness and energy: our nature, the name which we give to the Force of being in us in its actual and potential play and power, is complex in its ordering of consciousness, complex in its instrumentation of force. Every discovered or discoverable term and circumstance of that complexity which we can get into working order, we need to actualise in the highest and finest values possible to us and to use in its widest and richest powers for the one object. That object is to become, to be conscious, to increase continually in our realised being and awareness of self and things, in our actualised force and joy of being, and to express that becoming dynamically in such an action on the world and ourselves that we and it shall grow more and always yet more towards the highest possible reach, largest possible breadth of universality and infinity. All man's age-long effort, his action, society, art, ethics, science, religion, all the manifold activities by which he expresses and increases his mental, vital, physical, spiritual existence, are episodes in the vast drama of this endeavour of Nature and have behind their limited apparent aims no other true sense or foundation. For the individual to arrive at the divine universality and supreme infinity, live in it, possess it, to be, know, feel and express that alone in all his being, consciousness, energy, delight of being is what the ancient seers of the Veda meant by the Knowledge; that was the Immortality which they set before man as his divine culmination.

But by the nature of his mentality, by his inlook into himself and his outlook on the world, by his original limitation in both through sense and body to the relative, the obvious and the apparent, man is obliged to move step by step and at first obscurely and ignorantly in this immense evolutionary movement. It is not possible for him to envisage being at first in the completeness of its unity: it presents itself to him through diversity, and his search for knowledge is preoccupied with three principal categories which sum up for him all its diversity; himself, - man or individual soul, - God, and Nature. The first is that of which alone he is directly aware in his normal ignorant being; he sees himself, the individual, separate apparently in its existence, yet always inseparable from the rest of being, striving to be sufficient, yet always insufficient to itself, since never has it been known to come into existence or to exist or to culminate in its existence apart from the rest, without their aid and independently of universal being and universal nature. Secondly, there is that which he knows only indirectly by his mind and bodily senses and its effects upon them, yet must strive always to know more and more completely: for he sees also this rest of being with which he is so closely identified and yet from which he is so separate, - the cosmos, world, Nature, other individual existences whom he perceives as always like himself and yet always unlike; for they are the same in nature even to the plant and the animal and yet different in nature. Each seems to go its own way, to be a separate being, and yet each is impelled by the same movement and follows in its own grade the same vast curve of evolution as himself. Finally, he sees or rather divines something else which he does not know at all except quite indirectly; for he knows it only through himself and that at which his being aims, through the world and that at which it seems to point and which it is either striving obscurely to reach and express by its imperfect figures or, at least, founds them without knowing it on their secret relation to that invisible Reality and occult Infinite.

This third and unknown, this tertium quid, he names God; and by the word he means somewhat or someone who is the Supreme, the Divine, the Cause, the All, one of these things or all of them at once, the perfection or the totality of all that here is partial or imperfect, the absolute of all these myriad relativities, the Unknown by learning of whom the real secret of the known can become to him more and more intelligible. Man has tried to deny all these categories, - he has tried to deny his own real existence, he has tried to deny the real existence of the cosmos, he has tried to deny the real existence of God. But behind all these denials we see the same constant necessity of his attempt at knowledge; for he feels the need of arriving at a unity of these three terms, even if it can only be done by suppressing two of them or merging them in the other that is left. To do that he affirms only himself as cause and all the rest as mere creations of his mind, or he affirms only Nature and all the rest as nothing but phenomena of Nature-Energy, or he affirms only God, the Absolute, and all the rest as no more than illusions which That thrusts upon itself or on us by an inexplicable Maya. None of these denials can wholly satisfy, none solves the entire problem or can be indisputable and definitive, - least of all the one to which his sense-governed intellect is most prone, but in which it can never persist for long; the denial of God is a denial of his true quest and his own supreme Ultimate. The ages of naturalistic atheism have always been short-lived because they can never satisfy the secret knowledge in man: that cannot be the final Veda because it does not correspond with the Veda within which all mental knowledge is labouring to bring out; from the moment that this lack of correspondence is felt, a solution, however skilful it may be and however logically complete, has been judged by the eternal Witness in man and is doomed: it cannot be the last word of Knowledge.

Man as he is is not sufficient to himself, nor separate, nor is he the Eternal and the All; therefore by himself he cannot be the explanation of the cosmos of which his mind, life and body are so evidently an infinitesimal detail. The visible cosmos too, he finds, is not sufficient to itself, nor does it explain itself even by its unseen material forces; for there is too much that he finds both in the world and in himself which is beyond them and of which they seem only to be a face, an epidermis or even a mask. Neither his intellect, nor his intuitions, nor his feeling can do without a One or a Oneness to whom or to which these worldforces and himself may stand in some relation which supports them and gives them their significance. He feels that there must be an Infinite which holds these finites, is in, behind and about all this visible cosmos, bases the harmony and interrelation and essential oneness of multitudinous things. His thought needs an Absolute on which these innumerable and finite relativities depend for their existence, an ultimate Truth of things, a creating Power or Force or a Being who originates and upholds all these innumerable beings in the universe. Let him call it what he will, he must arrive at a Supreme, a Divine, a Cause, an Infinite and Eternal, a Permanent, a Perfection to which all tends and aspires, or an All to which everything perpetually and invisibly amounts and without which they could not be.

Yet even this Absolute he cannot really affirm by itself and to the exclusion of the two other categories; for then he has only made a violent leap away from the problem he is here to solve, and he himself and the cosmos remain an inexplicable mystification or a purposeless mystery. A certain part of his intellect and his longing for rest may be placated by such a solution, just as his physical intelligence is easily satisfied by a denial of the Beyond and a deification of material Nature; but his heart, his will, the strongest and intensest parts of his being remain without a meaning, void of purpose or justification, or become merely a random foolishness agitating itself like a vain and restless shadow against the eternal repose of the pure Existence or amidst the eternal inconscience of the universe. As for the cosmos, it remains there in the singular character of a carefully constructed lie of the Infinite, a monstrously aggressive and yet really non-existent anomaly, a painful and miserable paradox with false shows of wonder and beauty and delight. Or else it is a huge play of blind organised Energy without significance and his own being a temporary minute anomaly incomprehensibly occurring in that senseless vastness. That way no satisfying fulfilment lies for the consciousness, the energy that has manifested itself in the world and in man: the mind needs to find something that links all together, something by which Nature is fulfilled in man and man in Nature and both find themselves in God, because the Divine is ultimately self-revealed in both man and Nature.

An acceptance, a perception of the unity of these three categories is essential to the Knowledge; it is towards their unity as well as their integrality that the growing self-consciousness of the individual opens out and at which it must arrive if it is to be satisfied of itself and complete. For without the realisation of unity the knowledge of none of the three can be entire; their unity is for each the condition of its own integrality. It is, again, by knowing each in its completeness that all three meet in our consciousness and become one; it is in a total knowledge that all knowing becomes one and indivisible. Otherwise it is only by division and rejection of two of them from the third that we could get at any kind of oneness. Man therefore has to enlarge his knowledge of himself, his knowledge of the world and his knowledge of God until in their totality he becomes aware of their mutual indwelling and oneness. For so long as he knows them only in part, there will be an incompleteness resulting in division, and so long as he has not realised them in a reconciling unity, he will not have found their total truth or the fundamental significances of existence.

This is not to say that the Supreme is not self-existent and self-sufficient; God exists in Himself and not by virtue of the cosmos or of man, while man and cosmos exist by virtue of God and not in themselves except in so far as their being is one with the being of God. But still they are a manifestation of the power of God and even in His eternal existence their spiritual reality must in some way be present or implied, since otherwise there would be no possibility of their manifestation or, manifested, they would have no significance. What appears here as man is an individual being of the Divine; the Divine extended in multiplicity is the Self of all individual existences.97 Moreover, it is through the knowledge of self and the world that man arrives at the knowledge of God and he cannot attain to it otherwise. It is not by rejecting God's manifestation, but by rejecting his own ignorance of it and the results of his ignorance, that he can best lift up and offer the whole of his being and consciousness and energy and joy of being into the Divine Existence. He may do this through himself, one manifestation, or he may do it through the universe, another manifestation. Arriving through himself alone, it is possible for him to plunge into an individual immergence or absorption in the Indefinable and to lose the universe. Arriving through the universe alone, he can sink his individuality either in the impersonality of universal being or in a dynamic self of universal Conscious-Force; he merges into the universal self or he becomes an impersonal channel of the cosmic Energy. Arriving through the equal integrality of both and seizing through them and beyond them on all the aspects of the Divine, he exceeds both and fulfils them in that exceeding: he possesses the Divine in his being, even as he is enveloped, penetrated, pervaded, possessed by the Divine Being, Consciousness, Light, Power, Delight, Knowledge; he possesses God in himself and God in the universe. The All-Knowledge justifies to him its creation of himself and justifies by him perfected its creation of the world it has made. All this becomes entirely real and effective by an ascension into a supramental and supreme supernature and the descent of its powers into the manifestation; but even while that consummation is still difficult and distant, the true knowledge can be made subjectively real by a spiritual reflection or reception in mind-life-body Nature.

But this spiritual truth and true aim of his being is not allowed to appear till late in his journey: for the early preparatory business of man in the evolutionary steps of Nature is to affirm, to make distinct and rich, to possess firmly, powerfully and completely his own individuality. As a consequence, he has in the beginning principally to occupy himself with his own ego. In this egoistic phase of his evolution the world and others are less important to him than himself, are indeed only important as aids and occasions for his self-affirmation. God too at this stage is less important to him than he is to himself, and therefore in earlier formations, on the lower levels of religious development, God or the gods are treated as if they existed for man, as supreme instruments for the satisfaction of his desires, his helpers in his task of getting the world in which he lives to satisfy his needs and wants and ambitions. This primary egoistic development with all its sins and violences and crudities is by no means to be regarded, in its proper place, as an evil or an error of Nature; it is necessary for man's first work, the finding of his own individuality and its perfect disengagement from the lower subconscient in which the individual is overpowered by the mass consciousness of the world and entirely subject to the mechanical workings of Nature. Man the individual has to affirm, to distinguish his personality against Nature, to be powerfully himself, to evolve all his human capacities of force and knowledge and enjoyment so that he may turn them upon her and upon the world with more and more mastery and force; his self-discriminating egoism is given him as a means for this primary purpose. Until he has thus developed his individuality, his personality, his separate capacity, he cannot be fit for the greater work before him or successfully turn his faculties to higher, larger and more divine ends. He has to affirm himself in the Ignorance before he can perfect himself in the Knowledge.

For the initiation of the evolutionary emergence from the Inconscient works out by two forces, a secret cosmic consciousness and an individual consciousness manifest on the surface. The secret cosmic consciousness remains secret and subliminal to the surface individual; it organises itself on the surface by the creation of separate objects and beings. But while it organises the separate object and the body and mind of the individual being, it creates also collective powers of consciousness which are large subjective formations of cosmic Nature; but it does not provide for them an organised mind and body, it bases them on the group of individuals, develops for them a group mind, a changing yet continuous group body. It follows that only as the individuals become more and more conscious can the group-being also become more and more conscious; the growth of the individual is the indispensable means for the inner growth as distinguished from the outer force and expansion of the collective being. This indeed is the dual importance of the individual that it is through him that the cosmic spirit organises its collective units and makes them self-expressive and progressive and through him that it raises Nature from the Inconscience to the Superconscience and exalts it to meet the Transcendent. In the mass the collective consciousness is near to the Inconscient; it has a subconscious, an obscure and mute movement which needs the individual to express it, to bring it to light, to organise it and make it effective. The mass consciousness by itself moves by a vague, half-formed or unformed subliminal and commonly subconscient impulse rising to the surface; it is prone to a blind or half-seeing unanimity which suppresses the individual in the common movement: if it thinks, it is by the motto, the slogan, the watchword, the common crude or formed idea, the traditional, the accepted customary notion; it acts, when not by instinct or on impulse, then by the rule of the pack, the herd mentality, the type law. This mass consciousness, life, action can be extraordinarily effective if it can find an individual or a few powerful individuals to embody, express, lead, organise it; its sudden crowd-movements can also be irresistible for the moment like the motion of an avalanche or the rush of a tempest. The suppression or entire subordination of the individual in the mass consciousness can give a great practical efficiency to a nation or a community if the subliminal collective being can build a binding tradition or find a group, a class, a head to embody its spirit and direction; the strength of powerful military states, of communities with a tense and austere culture rigidly imposed on its individuals, the success of the great world-conquerors, had behind it this secret of Nature. But this is an efficiency of the outer life, and that life is not the highest or last term of our being. There is a mind in us, there is a soul and spirit, and our life has no true value if it has not in it a growing consciousness, a developing mind, and if life and mind are not an expression, an instrument, a means of liberation and fulfilment for the soul, the indwelling Spirit.

But the progress of the mind, the growth of the soul, even of the mind and soul of the collectivity, depends on the individual, on his sufficient freedom and independence, on his separate power to express and bring into being what is still unexpressed in the mass, still undeveloped from the subconscience or not yet brought out from within or brought down from the Superconscience. The collectivity is a mass, a field of formation; the individual is the diviner of truth, the form-maker, the creator. In the crowd the individual loses his inner direction and becomes a cell of the mass body moved by the collective will or idea or the mass impulse. He has to stand apart, affirm his separate reality in the whole, his own mind emerging from the common mentality, his own life distinguishing itself in the common lifeuniformity, even as his body has developed something unique and recognisable in the common physicality. He has, even, in the end to retire into himself in order to find himself, and it is only when he has found himself that he can become spiritually one with all; if he tries to achieve that oneness in the mind, in the vital, in the physical and has not yet a sufficiently strong individuality, he may be overpowered by the mass consciousness and lose his soul fulfilment, his mind fulfilment, his life fulfilment, become only a cell of the mass body. The collective being may then become strong and dominant, but it is likely to lose its plasticity, its evolutionary movement: the great evolutionary periods of humanity have taken place in communities where the individual became active, mentally, vitally or spiritually alive. For this reason Nature invented the ego that the individual might disengage himself from the inconscience or subconscience of the mass and become an independent living mind, life-power, soul, spirit, co-ordinating himself with the world around him but not drowned in it and separately inexistent and ineffective. For the individual is indeed part of the cosmic being, but he is also something more, he is a soul that has descended from the Transcendence. This he cannot manifest at once, because he is too near to the cosmic Inconscience, not near enough to the original Superconscience; he has to find himself as the mental and vital ego before he can find himself as the soul or spirit.

Still, to find his egoistic individuality is not to know himself; the true spiritual individual is not the mind ego, the life ego, the body ego: predominantly, this first movement is a work of will, of power, of egoistic self-effectuation and only secondarily of knowledge. Therefore a time must come when man has to look below the obscure surface of his egoistic being and attempt to know himself; he must set out to find the real man: without that he would be stopping short at Nature's primary education and never go on to her deeper and larger teachings; however great his practical knowledge and efficiency, he would be only a little higher than the animals. First, he has to turn his eyes upon his own psychology and distinguish its natural elements, - ego, mind and its instruments, life, body, - until he discovers that his whole existence stands in need of an explanation other than the working of the natural elements and of a goal for its activities other than an egoistic self-affirmation and satisfaction. He may seek it in Nature and mankind and thus start on his way to the discovery of his unity with the rest of his world: he may seek it in supernature, in God, and thus start on his way to the discovery of his unity with the Divine. Practically, he attempts both paths and, continually wavering, continually seeks to fix himself in the successive solutions that may be best in accordance with the various partial discoveries he has made on his double line of search and finding.

But through it all what he is in this stage still insistently seeking to discover, to know, to fulfil is himself; his knowledge of Nature, his knowledge of God are only helps towards selfknowledge, towards the perfection of his being, towards the attainment of the supreme object of his individual self-existence. Directed towards Nature and the cosmos, it may take upon itself the figure of self-knowledge, self-mastery - in the mental and vital sense - and mastery of the world in which we find ourselves: directed towards God, it may take also this figure but in a higher spiritual sense of world and self, or it may assume that other, so familiar and decisive to the religious mind, the seeking for an individual salvation whether in heavens beyond or by a separate immergence in a supreme Self or a supreme Non-Self, - beatitude or Nirvana. Throughout, however, it is the individual who is seeking individual self-knowledge and the aim of his separate existence, with all the rest, even altruism and the love and service of mankind, self-effacement or selfannihilation, thrown in - with whatever subtle disguises - as helps and means towards that one great preoccupation of his realised individuality. This may seem to be only an expanded egoism, and the separative ego would then be the truth of man's being persistent in him to the end or till at last he is liberated from it by his self-extinction in the featureless eternity of the Infinite. But there is a deeper secret behind which justifies his individuality and its demand, the secret of the spiritual and eternal individual, the Purusha.

It is because of the spiritual Person, the Divinity in the individual, that perfection or liberation - salvation, as it is called in the West - has to be individual and not collective; for whatever perfection of the collectivity is to be sought after, can come only by the perfection of the individuals who constitute it. It is because the individual is That, that to find himself is his great necessity. In his complete surrender and self-giving to the Supreme it is he who finds his perfect self-finding in a perfect self-offering. In the abolition of the mental, vital, physical ego, even of the spiritual ego, it is the formless and limitless Individual that has the peace and joy of its escape into its own infinity. In the experience that he is nothing and no one, or everything and everyone, or the One which is beyond all things and absolute, it is the Brahman in the individual that effectuates this stupendous merger or this marvellous joining, Yoga, of its eternal unit of being with its vast all-comprehending or supreme all-transcending unity of eternal existence. To get beyond the ego is imperative, but one cannot get beyond the self - except by finding it supremely, universally. For the self is not the ego; it is one with the All and the One and in finding it it is the All and the One that we discover in our self: the contradiction, the separation disappears, but the self, the spiritual reality remains, united with the One and the All by that delivering disappearance.

The higher self-knowledge begins therefore as soon as man has got beyond his preoccupation with the relation of Nature and God to his superficial being, his most apparent self. One step is to know that this life is not all, to get at the conception of his own temporal eternity, to realise, to become concretely aware of that subjective persistence which is called the immortality of the soul. When he knows that there are states beyond the material and lives behind and before him, at any rate a pre-existence and a subsequent existence, he is on the way to get rid of his temporal ignorance by enlarging himself beyond the immediate moments of Time into the possession of his own eternity. Another step forward is to learn that his surface waking state is only a small part of his being, to begin to fathom the abyss of the Inconscient and depths of the subconscient and subliminal and scale the heights of the superconscient; so he commences the removal of his psychological self-ignorance. A third step is to find out that there is something in him other than his instrumental mind, life and body, not only an immortal ever-developing individual soul that supports his nature but an eternal immutable self and spirit, and to learn what are the categories of his spiritual being, until he discovers that all in him is an expression of the spirit and distinguishes the link between his lower and his higher existence; thus he sets out to remove his constitutional self-ignorance. Discovering self and spirit he discovers God; he finds out that there is a Self beyond the temporal: he comes to the vision of that Self in the cosmic consciousness as the divine Reality behind Nature and this world of beings; his mind opens to the thought or the sense of the Absolute of whom self and the individual and the cosmos are so many faces; the cosmic, the egoistic, the original ignorance begin to lose the rigidness of their hold upon him. In his attempt to cast his existence into the mould of this enlarging self-knowledge his whole view and motive of life, thought and action are progressively modified and transformed; his practical ignorance of himself, his nature and his object of existence diminishes: he has set his step on the path which leads out of the falsehood and suffering of a limited and partial into the perfect possession and enjoyment of a true and complete existence.

In the course of this progress he discovers step by step the unity of the three categories with which he started. For, first, he finds that in his manifest being he is one with cosmos and Nature; mind, life and body, the soul in the succession of Time, the conscient, subconscient and superconscient, - these in their various relations and the result of their relations are cosmos and are Nature. But he finds too that in all which stands behind them or on which they are based, he is one with God; for the Absolute, the Spirit, the Self spaceless and timeless, the Self manifest in the cosmos and Lord of Nature, - all this is what we mean by God, and in all this his own being goes back to God and derives from it; he is the Absolute, the Self, the Spirit self-projected in a multiplicity of itself into cosmos and veiled in Nature. In both of these realisations he finds his unity with all other souls and beings, - relatively in Nature, since he is one with them in mind, vitality, matter, soul, every cosmic principle and result, however various in energy and act of energy, disposition of principle and disposition of result, but absolutely in God, because the one Absolute, the one Self, the one Spirit is ever the Self of all and the origin, possessor and enjoyer of their multitudinous diversities. The unity of God and Nature cannot fail to manifest itself to him: for he finds in the end that it is the Absolute who is all these relativities; he sees that it is the Spirit of whom every other principle is a manifestation; he discovers that it is the Self who has become all these becomings; he feels that it is the Shakti or Power of being and consciousness of the Lord of all beings which is Nature and is acting in the cosmos. Thus in the progress of our self-knowledge we arrive at that by the discovery of which all is known as one with our self and by the possession of which all is possessed and enjoyed in our own self-existence.

Equally, by virtue of this unity, the knowledge of the universe must lead the mind of man to the same large revelation. For he cannot know Nature as Matter and Force and Life without being driven to scrutinise the relation of mental consciousness with these principles, and once he knows the real nature of mind, he must go inevitably beyond every surface appearance. He must discover the will and intelligence secret in the works of Force, operative in material and vital phenomena; he must perceive it as one in the waking consciousness, the subconscient and the superconscient: he must find the soul in the body of the material universe. Pursuing Nature through these categories in which he recognises his unity with the rest of the cosmos, he finds a Supernature behind all that is apparent, a supreme power of the Spirit in Time and beyond Time, in Space and beyond Space, a conscious Power of the Self who by her becomes all becomings, of the Absolute who by her manifests all relativities. He knows her, in other words, not only as material Energy, Life-Force, Mind-Energy, the many faces of Nature, but as the power of Knowledge-Will of the Divine Lord of being, the Consciousness-Force of the self-existent Eternal and Infinite.

The quest of man for God, which becomes in the end the most ardent and enthralling of all his quests, begins with his first vague questionings of Nature and a sense of something unseen both in himself and her. Even if, as modern Science insists, religion started from animism, spirit-worship, demon-worship and the deification of natural forces, these first forms only embody in primitive figures a veiled intuition in the subconscient, an obscure and ignorant feeling of hidden influences and incalculable forces, or a vague sense of being, will, intelligence in what seems to us inconscient, of the invisible behind the visible, of the secretly conscious spirit in things distributing itself in every working of energy. The obscurity and primitive inadequacy of the first perceptions do not detract from the value or the truth of this great quest of the human heart and mind, since all our seekings - including Science itself - must start from an obscure and ignorant perception of hidden realities and proceed to the more and more luminous vision of the Truth which at first comes to us masked, draped, veiled by the mists of the Ignorance. Anthropomorphism is an imaged recognition of the truth that man is what he is because God is what He is and that there is one soul and body of things, humanity even in its incompleteness the most complete manifestation yet achieved here and divinity the perfection of what in man is imperfect. That he sees himself everywhere and worships that as God is also true; but here too he has laid confusedly the groping hand of Ignorance on a truth - that his being and the Being are one, that this is a partial reflection of That, and that to find his greater Self everywhere is to find God and to come near to the Reality in things, the Reality of all existence.

A unity behind diversity and discord is the secret of the variety of human religions and philosophies; for they all get at some image or some side clue, touch some portion of the one Truth or envisage some one of its myriad aspects. Whether they see dimly the material world as the body of the Divine, or life as a great pulsation of the breath of Divine Existence, or all things as thoughts of the cosmic Mind, or realise that there is a Spirit which is greater than these things, their subtler and yet more wonderful source and creator, - whether they find God only in the Inconscient or as the one Conscious in inconscient things or as an ineffable superconscious Existence to reach whom we must leave behind our terrestrial being and annul the mind, life and body, or, overcoming division, see that He is all these at once and accept fearlessly the large consequences of that vision, - whether they worship Him with universality as the cosmic Being or limit Him and themselves, like the Positivist, in humanity only or, on the contrary, carried away by the vision of the timeless and spaceless Immutable, reject Him in Nature and Cosmos, - whether they adore Him in various strange or beautiful or magnified forms of the human ego or for His perfect possession of the qualities to which man aspires, his Divinity revealed to them as a supreme Power, Love, Beauty, Truth, Righteousness, Wisdom, - whether they perceive Him as the Lord of Nature, Father and Creator, or as Nature herself and the universal Mother, pursue Him as the Lover and attracter of souls or serve Him as the hidden Master of all works, bow down before the one God or the manifold Deity, the one divine Man or the one Divine in all men or, more largely, discover the One whose presence enables us to become unified in consciousness or in works or in life with all beings, unified with all things in Time and Space, unified with Nature and her influences and even her inanimate forces, - the truth behind must ever be the same because all is the one Divine Infinite whom all are seeking. Because everything is that One, there must be this endless variety in the human approach to its possession; it was necessary that man should find God thus variously in order that he might come to know Him entirely. But it is when knowledge reaches its highest aspects that it is possible to arrive at its greatest unity. The highest and widest seeing is the wisest; for then all knowledge is unified in its one comprehensive meaning. All religions are seen as approaches to a single Truth, all philosophies as divergent view-points looking at different sides of a single Reality, all Sciences meet together in a supreme Science. For that which all our mind-knowledge and sense-knowledge and suprasensuous vision is seeking, is found most integrally in the unity of God and man and Nature and all that is in Nature.

The Brahman, the Absolute is the Spirit, the timeless Self, the Self possessing Time, Lord of Nature, creator and continent of the cosmos and immanent in all existences, the Soul from whom all souls derive and to whom they are drawn, - that is the truth of Being as man's highest God-conception sees it. The same Absolute revealed in all relativities, the Spirit who embodies Himself in cosmic Mind and Life and Matter and of whom Nature is the self of energy so that all she seems to create is the Self and Spirit variously manifested in His own being to His own conscious force for the delight of His various existence, - this is the truth of being to which man's knowledge of Nature and cosmos is leading him and which he will reach when his Natureknowledge unites itself with his God-knowledge. This truth of the Absolute is the justification of the cycles of the world; it is not their denial. It is the Self-Being that has become all these becomings; the Self is the eternal unity of all these existences, - I am He. Cosmic energy is not other than the conscious force of that Self-existent: by that energy It takes through universal nature innumerable forms of itself; through its divine nature It can, embracing the universal but transcendent of it, arrive in them at the individual possession of its complete existence, when its presence and power are felt in one, in all and in the relations of one with all; - this is the truth of being to which man's entire knowledge of himself in God and in Nature rises and widens. A triune knowledge, the complete knowledge of God, the complete knowledge of himself, the complete knowledge of Nature, gives him his high goal; it assigns a vast and full sense to the labour and effort of humanity. The conscious unity of the three, God, soul and Nature, in his own consciousness is the sure foundation of his perfection and his realisation of all harmonies: this will be his highest and widest state, his status of a divine consciousness and a divine life and its initiation the starting-point for his entire evolution of his self-knowledge, world-knowledge, God-knowledge.